What brought you to the Netherlands?

I came to the Netherlands in 1972, entirely by chance. It wasn’t a choice. In 1970, the Romanian Ministry of Health received several offers for international scholarships for young specialists. Of course, there were some conditions: they had to be well-prepared professionally – and this was to be backed up by their exams and competition results –, and they had to master a number of foreign languages, particularly English, German, or French.

In 1970, I was called to the Ministry and I was told that I had been included on a list of young specialists who had been considered for potential scholarships abroad. I was a young radiologist, I had just finished my specialty, and I was working at one of the polyclinics of the Brâncoveanu Hospital (built at the end of the 19th century on behalf of a Romanian aristocrat, it was initially intended for destitute people, and it was demolished by the communist regime in 1984, ed.). I was told not to expect too much.

After almost a year, I was called again to the Ministry, and I was told: “You know, doctor, that thing with England is not happening anymore.” But I didn’t know anything about any “thing with England”. I was in the University fencing team – I’m not digressing, there’s a link to my story –, and in December 1971 I had went with the team to a contest in Poland. After that contest, when I returned to work at the polyclinic, I found a note saying I had to call the Ministry. The one who picked up was Mrs. Marinescu – the officer responsible for the relationship with the specialists and foreign countries –, who said: “Where have you been, sir? Monday, the 5th of January, you have to be in the Netherlands. Your passport and plane ticket are ready.” And that’s how I found out, about midway into December, that in two weeks’ time I had to leave and spend six months in the Netherlands. So that’s how I got here.

And you also remained in the Netherlands.

Yes, but how I got to remain here is a different story. In 1972, after his visit to China and North Korea, Nicolae Ceaușescu returned very impressed by what he had seen there – it was that period of maximum dictatorship of the proletariat in those countries, there was no sign of relaxation – and he set off the so-called cultural mini-revolution in România. In other words, he put the clamps on all kinds of human rights – the freedom of speech, of movement – and he also took advantage of the internal power struggle to get rid of political rivals and surround himself only with his own people. With that backdrop in mind, I began to think about not going back to Romania anymore. My boss at the place where I worked in Amsterdam thought that I was well-prepared professionally and he offered me to continue to work for him, at which point I was confronted with a dilemma: what was I to do?

Nowadays, your generation can leave and come back several times a year, but in those circumstances, in Romania, to have remained in another country meant an act of treason, liable to imprisonment, and seeing your family again became almost impossible. On top of that, the family that remained behind would suffer when a family member stayed abroad.

I was 30 years old when I remained in the Netherlands. And I stayed because I was offered the opportunity of a dream career, which was impossible to achieve in Romania: to work in a very well equipped university hospital that was well-known in Europe – Wilhelmina Gasthuis –, together with internationally-renowned healthcare professionals. The head of the radiology department in Amsterdam was a professor known worldwide for several inventions that truly changed the course in which our profession developed. So it was an honor for me, but also a remarkable challenge, and I decided to remain.

And to make it clear that the Netherlands wasn’t a choice, I’ll tell you that during my scholarship and afterward, I prepared for the US medical entrance exam, which I passed. Back then, I was thinking about pursuing a career in the United States. Eventually, I didn’t go there anymore, but the exam did me good, because within a year I revised and updated all the knowledge learned during med school, as it’s an extremely difficult exam.

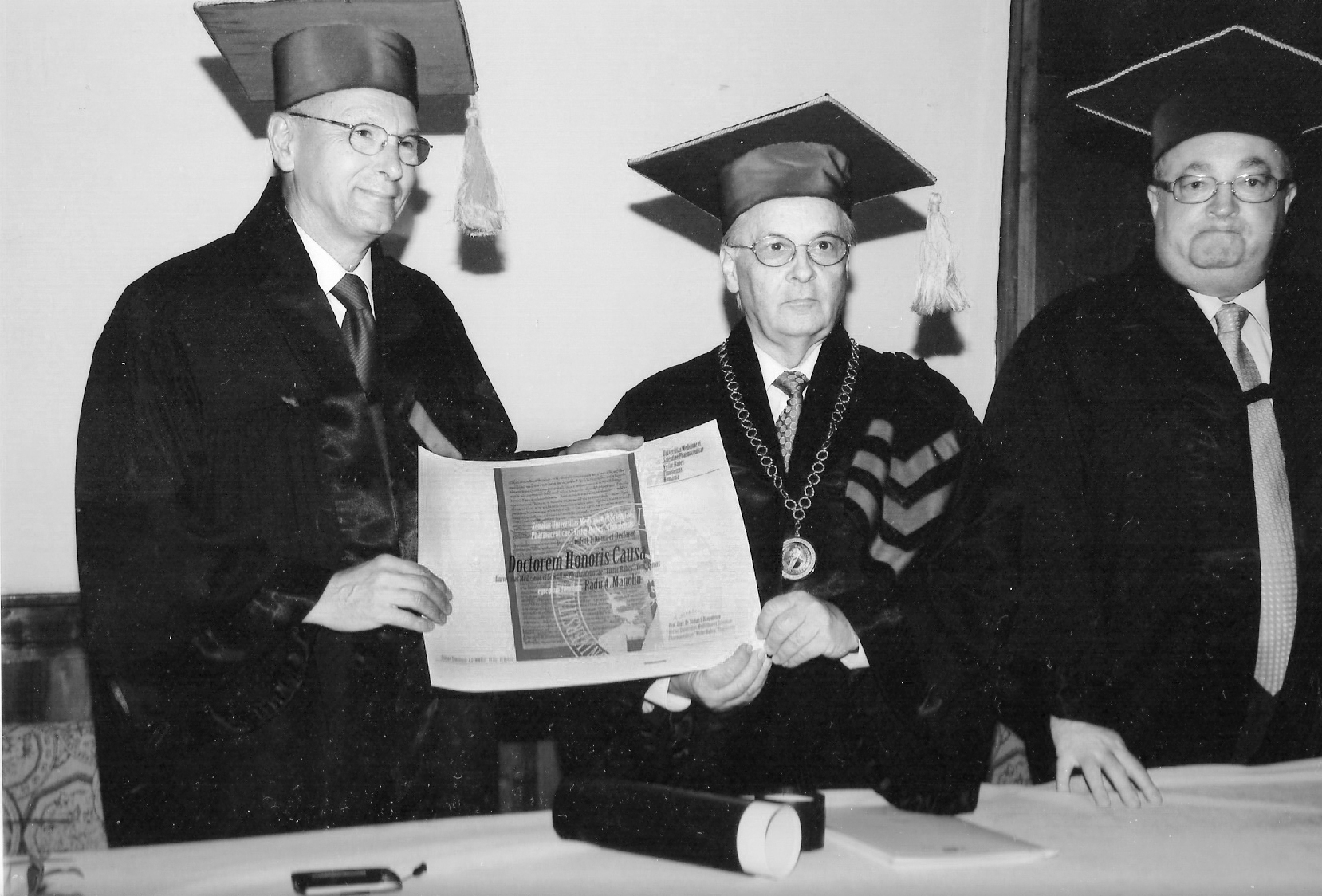

But what was the procedure to have your doctor’s degree recognized, given that Romania was still far from being in the European Union?

At that time, this recognition of a specialist’s diploma was up to the professor who was the head of the clinic and who had been authorized by the Ministry to grant the specialty to the healthcare professionals. The people at the hospital in Amsterdam considered that after a year I was at the same level as them. They put me to work from day one. I have to say, however, that during the first year I worked tremendously hard. I was alone, I had no family, and there was a difference compared to Bucharest, where a radiologist left home at 13:30, while here I worked until 18:00. So, during the day I was at the clinic, while in the evening I was learning Dutch and I was preparing for the American exam. After a year, I worked side by side with my Dutch colleagues, and after a year and a half, I became a Dutch specialist, with the professor’s approval.

What was it like in the beginning here?

Struggling with loneliness was an issue, sometimes you can suffer from loneliness. At that time, there weren’t that many Romanians in the Netherlands, and I would go for weeks, even months, without saying a single Romanian word or hearing anyone speak Romanian around me. A few Dutch people took pity on me, especially Tilly Klomp, a lady who was born in Romania, in the expat group from the Dutch community at Shell-Astra Română, the company that used to exploit the Romanian oil before the war. This lady did so many good deeds for Romania, I have a very fond memory of her.

She was the one who brought me the papers that I needed from Romania, which she took from my mother. I would talk to my mother on the phone. In the beginning, she was very scared, then very sad, she also went through the stages of a loss. I managed to see her again after the earthquake in 1977, thanks to the intervention of Ruud Lubbers, the Dutch Minister of Economic Affairs, later Prime Minister. I had found out that he was going to pay a visit to Romania for trade contracts – back then, Romania had important contracts with the Netherlands – and I sent him a letter in which I told him who I was – meanwhile, I had been appointed Head of Department at the Leiden University Medical Center – and I asked him to help me see my mother. I also told him that I understood that officially he couldn’t do much, but that unofficially there are ways that work. After his visit to Romania, my mother was called to the passport office on the Nicolae Iorga street and she was told that her request for a passport had been approved – a request that she had not even submitted after the last one had been declined. And that’s how my mother came to the Netherlands, wearing an arm cast due to a fracture caused by the earthquake.

You set on this path alone, that means that you must have met Mrs. Anca Manoliu here.

We already knew each other when we were still in Romania. Anca received a scholarship, as well, but in Paris, and it was also not paid by the Romanian government. Anca is a psychologist. During that period we saw each other a lot and we spent a lot of time together. I invited her to the Netherlands, I also went to Paris, and we decided to get married. That was 45 years ago.

How do you look back at all these years?

I don’t regret even for a second the decision I made then. I can’t say that it was entirely my merit, in life you have to have also a little bit of luck, have circumstances in your favor, have some doors open. In Romania, I had the feeling that I was knocking only on closed doors that never opened. I wanted an university career, and judging by the results I got in all the exams and competitions, I was entitled to that, but nothing opened for me. I saw nothing but people looking away, whereas, in the Netherlands, I saw people looking at me. The doors opened and the journey has been wonderful.

It was the moment when I cut ties with Romania, which meant that for almost 18 years, I could not go there anymore. Then, the liberation moment came, when communism fell and I could travel to Romania again, which was on the 1st of January, in 1990. Together with a Dutchman, I went around Bucharest for a week and we interviewed several representative people from the former communist regime who had been involved in the change, but also a few people who had suffered a lot during the communist period. The interviews were commissioned by VPRO (one of the Dutch public broadcasters, ed.) and they were broadcasted over several episodes. I was the interpreter of that young journalist and the recordings still exist.

How did you adjust to the Dutch society?

You can’t grasp the Dutch society straight away. Initially, on a superficial level, everything seemed normal, that they’re people just like us, that they laugh the same way as we do, they react like us. Gradually, after many years, I discovered that it’s a culture with many values that are in many ways different from ours. But it wasn’t a cultural shock, more of a gradual discovery.

I discovered that “civic engagement” isn’t just words void of meaning. Civic engagement means being interested in what’s going on around you and believing that you too can contribute something for the greater good. In Romania, during the communist regime – but I notice that even now it’s the same –, people suffered – and still do – from some sort of cynicism. In Romania, it’s hard to find true civic engagement. Here, those are not just empty words.

In the medical field, there is a continuity in caring for the patient, meaning that the patient, the ill person, is deliberately transferred, they’re not left in the void. In Romania, even now you still feel that patients are being left to chance between one specialist and another, between one hospital and another – I know this because I still have relatives and friends there. Here, the system takes care of you and doesn’t leave you high and dry.

Another aspect: Romanians have no financial and administrative training. Neither did I. The Dutch receive training from a young age, when they’re in school. I don’t know if it’s still like this today, but before, when our girls went to school, it used to be that they had a class that was called hoofdrekenen (mental calculation, ed.), meaning doing calculations using just your brain, which is very important for the Dutch, who are a nation of traders. We didn’t have that in Romania and I think that even now something like this is not being taught. But, of course, now we have calculators.

Back in my day, there was a word we would use as a tongue-in-cheek, so to say: the word “attitude”. During our evaluation and self-evaluation meetings, you got to hear people say: “The comrade has a wrong attitude.” Or: “The comrade’s attitude is not in line with the principles of our proletarian state.” Or: “The comrade has a bourgeois attitude.” The worst was when someone would say about you that you had an “unhealthy attitude”. We regarded these expressions as a means of terror, which you can only laugh about because it can’t be helped. In the Netherlands, an “attitude” is something real and important. A doctor is being taught about four things during their medical training: knowledge, skills, empathy, and attitude. The attitude is one of the four elements of the Dutch culture. In which school or university in Romania do you learn that an engineer must have an engineer’s attitude with their clients, and a doctor a doctor’s attitude? That’s not necessarily the same.

How do you feel in the Dutch society?

I feel at home. And it’s only natural that it is like that after having functioned and progressed in this society for 45 years. What does it mean to feel at home? It means being able to understand those around you, to understand how the society’s wheels are turning, to understand the codes that exist.

Of course I speak Dutch with an accent and they immediately realize I’m not a native, but it doesn’t matter. The Dutch society has changed very much during these 45 years. When I came here, there weren’t that many foreigners, [meanwhile] the society has diversified considerably, it has become secularized.

What does success mean to you?

Success means that your wishes and plans become reality. There are all kinds of measurement units, such as, for instance, the number of records sold, or the rating that famous people have on TV. For those who are not public figures, success is represented by a very personal measurement unit, which has to do with being self-contented.

I think it’s a very difficult question because the answers could be hypocritical. But you must have some dreams, you must want something. You don’t want anything, you don’t get anything.

What kind of a relationship do you have with the Romanian community in the Netherlands?

There is a Dutch idiom that I can’t translate easily in Romanian, there’s a lot of los zand (als los zand aan elkaar hangen – without cohesiveness, ed.), meaning it’s very fragmented, there’s very little collective spirit. I don’t expect any unity, because there’s a great diversity of personalities, professional backgrounds, education, and motivations. I’m now starting to see that it’s beginning to be organized. Take, for instance, the Romanians for Romanians in the Netherlands Foundation (ROMPRO, ed.). Over the years, there have been many attempts, but now I see that something has begun to bind, there are more Romanians who seek to get in touch with the others. And where there’s a desire to come into contact, the chance of survival of certain foundations and cultural activities increases.

On top of that, during the time when I came here, I would avoid the Embassy, it was like a tool of the communist state, I equaled it to espionage, fairly or unfairly, that was the perception. Only after 1990 did the Embassy gradually regain the trust of the Romanians in the Netherlands. Now, the Embassy has a positive role.

Another important factor is the church. Many Romanians are religious, they’re believers. The first church in the Netherlands was established by the priest [Ioan] Dură in Schiedam.

We never ran away from Romanians. We have a pretty large group of Romanian friends, I frequently take part in the activities of the community, and many times I even offer financial support to certain cultural activities.

And I would like to mention one more thing. In 1987, we set up – I didn’t do it alone – the Roemenië Comité, a political forum to protest against the communism in Romania, a foundation that wanted to draw the public’s attention to the unacceptable things that were happening there. Such foundations were established also for other countries: Angola, South Africa, and other former communist states. Our chairman was Sorin Alexandrescu, who returned to Romania, Jan Willem Bos was the secretary, and I was the vice president. We even issued a magazine, Roemenië Comité, for twenty years. During that time, we raised a considerable amount of money, with which we financed cultural activities related to Romania. Recently, we dissolved this entity, as it had lost its purpose.

What would you advise a Romanian who would like to come to the Netherlands now?

Think well if you cannot build in Romania a life that can bring you fulfillment and satisfaction. If, however, you decide to leave, you have to know very well what you want, you have to know your skills very well, and you have to be able to adapt and change habits that have been deeply rooted in you. If you want to stay in the Netherlands, you must know why. And if you choose to stay in the long term, invest a lot in learning the Dutch language.

An interview by Claudia Marcu

Translation by Mihaela Nita

Photo-portrait by Cristian Călin – www.cristiancalin.video

photos from the personal archive, edited by Alexandru Matei